Indoor amusement parks are found all over the globe. From Nickelodeon Universe in the USA to Warner Brothers World in Abu Dhabi, they provide thrill-seekers a weatherproof option for their adventures.

Interestingly, despite England’s notorious weather, it currently lacks such an attraction. However, this wasn’t always the case. Not so long ago Gateshead was the proud host of Metroland, Europe’s largest indoor theme park. It delighted visitors for two decades before its closure in 2008 and was subsequently replaced by a cinema.

The concept of enclosed shopping malls first emerged in the USA during the mid-1950s. They quickly gained popularity, with retail outlets migrating from city centres to these new commercial hubs. By the 1980s, these malls had become prime spots for shopping and socialising. Over here in England, the first major indoor shopping centre opened its doors in 1964 in the Midlands.

Taking a leaf out of America’s book, the Bull Ring in Birmingham offered a glimpse into the future of shopping with its air-conditioned, temperature-regulated halls. Hailed as the largest indoor shopping centre outside the USA, the Bull Ring quickly became a game-changer. Every day, thousands poured in from Birmingham and beyond, arriving by train at New Street Station, ready to explore the myriad of shops.

While high streets still dominated the retail landscape, the allure of shopping centres was growing. Over the next decade, each new centre seemed to outdo the last in size and variety. By the mid-1980s, shopping centres had become a familiar sight in the UK, often integrated into town centres.

1976 marked a milestone with the opening of Brent Cross in North London. Dubbed the UK’s first American-style mall, it set a new precedent. Meanwhile, up North, a different kind of retail revolution was brewing. Plans for a groundbreaking project were set in motion in 1979. This wasn’t just going to be the largest shopping centre in the UK but in all of Europe, and it would take seven years to turn this ambitious idea into reality.

In Gateshead, an ambitious vision was taking shape. Local businessman John Hall, the managing director of Cameron Hall, was set on transforming the neglected Dunston riverside into Europe’s premier destination for shopping and leisure. His plans were far from ordinary; envisioning dry ski slopes, fun zones for kids, and even paddle steamers serving food on the adjacent lake. This wasn’t your typical retail project; it was a dream to create something the North East could truly be proud of.

With a budget exceeding £50 million, the development was scheduled to unfold in phases over several years. John Hall’s mantra was clear: look to the future and evolve to attract people. The MetroCentre wasn’t going to be just another shopping complex. It was envisioned as a standard-bearer for the North East, a place made with the people in mind, not just profits. More than a shopping destination, it was to be an experience, a culmination of ideas from John and his wife Mae’s travels around the globe.

North American inspiration

John and Mae Hall’s visit to the Eaton Centre in Toronto and the West Edmonton Mall in Alberta, Canada, left a lasting impression. At the time, the West Edmonton Mall was the largest shopping mall in the world, and it wasn’t just its size that caught their attention. It was the vibe, the energy that these places exuded, something they were determined to replicate back in the UK.

The West Edmonton Mall was home to Fantasyland (later renamed Galaxyland), an indoor amusement park that opened in 1983. This particular feature struck a chord with John Hall. He saw the potential for something similar in Gateshead, a perfect setting for an indoor amusement park of their own.

Inspired by the Canadian model, John envisioned a place where the excitement and joy of an amusement park could be experienced year-round, unaffected by the unpredictable British weather. This idea was about to add a whole new dimension to the shopping and leisure experience they were crafting for the North East.

The MetroCentre was set to redefine shopping with its colossal structure. At its launch, it boasted four major anchor stores and nearly 200 shops, embodying the concept of one-stop shopping. The design was striking – spacious walkways, abundant natural light, and themed areas that were more than just retail spaces. They were destinations in themselves, places that beckoned people to come and spend time.

Throughout 1985, the buzz around the MetroCentre grew as big retail names like Marks & Spencer, Carrefour, Argos, and House of Fraser confirmed their presence. John Hall was confident this project would reshape UK retailing, signalling a shift away from traditional city centre shopping.

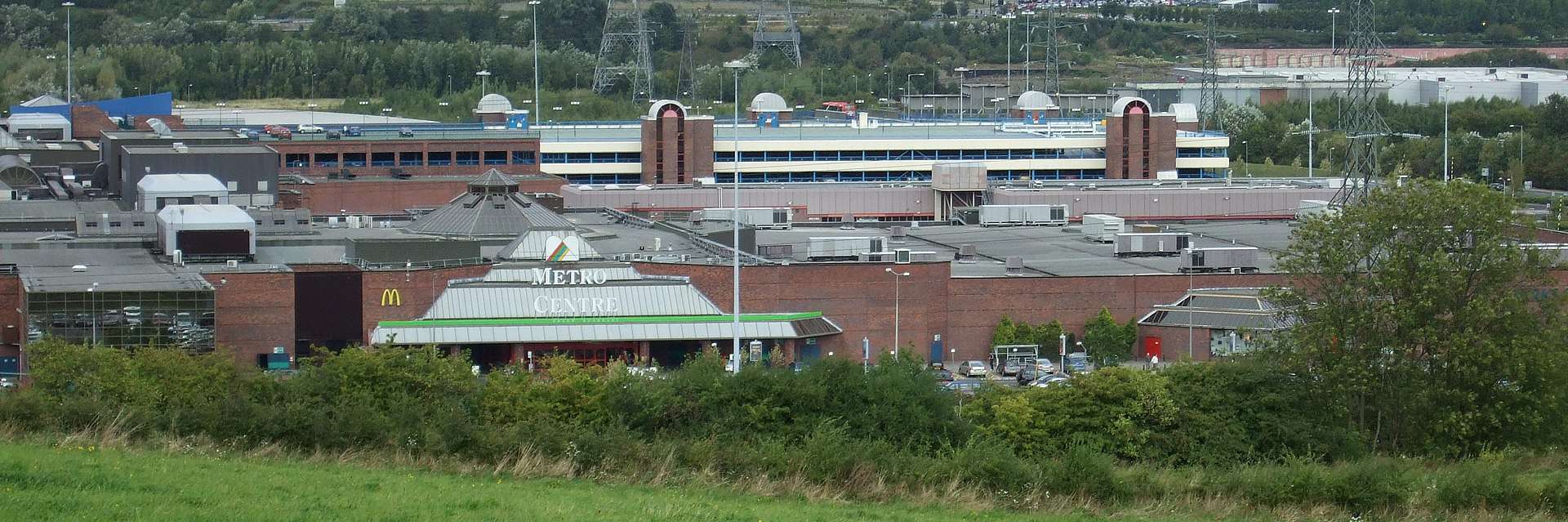

Funded by the Church Commissioners of England, the first phase, known as The Red Mall, opened in April 1986. It wasn’t just a new shopping centre; it was a catalyst for economic revitalisation in the area. Overnight, the MetroCentre altered the retail landscape in the UK, setting a benchmark that future shopping centres would strive to meet.

More than a shopping centre

But the MetroCentre was never meant to be just about shopping. It was an entire experience, a fact that became even clearer when the other wings opened. In 1988, a new chapter began with the launch of Metroland, a £20 million venture. Inspired by Fantasyland, this would become Europe’s largest indoor amusement park – a dazzling addition that transformed the MetroCentre into much more than a retail destination.

Rush & Tompkins, the same team behind the shopping centre, designed Metroland. This amusement park, nestled within the Yellow Mall section, was not merely an add-on; it was an integral part of the MetroCentre experience, especially for kids. General admission was free to just walk around, allowing families to stroll in and immerse themselves in the fun. Initially managed by Forrec, the team behind West Edmonton Mall, Metroland was destined to become a hit and despite some hiccups with ride breakdowns on the opening day, the park quickly became a favourite.

Visitors were greeted by a mirror-clad, 55-foot building, housing a variety of attractions. Next to it lay a state-of-the-art arcade and an array of food options. In 1989, Funday LTD took over the management, injecting an additional £1 million into the park.

Rides and attractions at Metroland

Stepping off the escalator into Metroland, visitors found an unchanged yet always thrilling world. The park boasted 12 rides, offering something for everyone. Attractions included the delightful Waveswinger, the adventurous Pirate Ship, the Balloons Ferris Wheel, the Disco Dodgems along with several slides.

The crown jewel of Metroland was its roller coaster. More than just a ride, it was a rite of passage for youngsters in the North-East. This Zierer Tivoli custom coaster, spanning 1194 feet of track and soaring up to 48 feet, offered a 60-second whirlwind ride at speeds nearing 27 mph. For many children, that moment of anticipation as they plunged into the tunnel was a mix of fear and excitement, a memory etched in their minds forever.

Two popular attractions, The Whirling Waltzer and Monty Zoomers, were initially operated by external companies. However, in April 2003, Metroland took over these rides, integrating them into the park’s wristband pricing scheme.

The ‘New’ Metroland

Funday LTD, the management company of Metroland, found themselves at odds with the MetroCentre’s owners over service charge calculations. This dispute escalated to court, leading to Funday withholding payments until a resolution. Amidst these tensions, new management stepped in.

In August 1996, Metroland underwent a rebranding as ‘The New Metroland’ under the stewardship of Arlington Leisure. Arlington, known for their expertise in running family entertainment centres across the UK, invested over £2 million in refurbishing the park. The roller coaster, a beloved staple of Metroland, was rechristened ‘The New Roller Coaster’. The change was nominal – the ride remained the same, save for a fresh coat of paint on the supports. This rebranding effort was a clever strategy to rejuvenate Metroland’s appeal with minimal alterations.

Despite these changes being largely cosmetic, they did attract additional visitors. Metroland’s year-round operation set it apart from other UK amusement parks, which typically shut during the winter. Its popularity increased, with millions flocking to the park each year. By 2005, Metroland continued to be a magnet for those visiting the shopping centre, offering a nostalgic slice of the 80s and 90s. With over 1.2 million people annually paying for rides, it ranked among the top 10 tourist attractions in the UK.

Metroland’s efforts to introduce new attractions hit a snag due to lease disagreements with Capital Shopping Centres, the new owners of the Metro Centre. As the shopping centre underwent gradual updates over the years, many of its unique themes and leisure elements were slowly phased out. Yet, Metroland remained relatively unchanged for two decades.

Decline and eventual closure

Despite its enduring popularity, the park began to show its age, and its appeal started to wane. Amidst growing concerns and rumours about its closure, a significant campaign to save Metroland emerged, gaining widespread attention. Even Sir John Hall, the man behind the original idea for the MetroCentre, lent his support.

He reminisced about his vision for the project, inspired by international models where shopping was a family affair. For Hall, the MetroCentre was always meant to be more than just a retail hub. It was a place for leisure, a destination for everyone, not just a series of shops. This sentiment resonated deeply with those who saw Metroland as an integral part of the MetroCentre’s identity.

Despite a spirited campaign with thousands of signatures and numerous letters of objection, efforts to save Metroland ultimately fell short. In late 2007, the inevitable was confirmed: Metroland would close. Its final day of operation was slated for Sunday, April 20th, 2008. Two months later, Arlington Leisure relinquished the property back to Capital Shopping Centres, and the Yellow Mall, once home to the vibrant amusement park, was set for a complete makeover. Metroland, a fond part of many childhoods, was destined to become a cherished memory.

In a touching farewell, the park hosted a ‘last ride’ weekend. For a mere £5, visitors could enjoy unlimited rides, with all proceeds going to charity. The end was bittersweet; rides and attractions were sold off, and the once-bustling area was emptied. Even the signs and interior fittings were auctioned. The closure impacted 120 staff members, many of whom had been part of the Metroland family for years. The space that once echoed with the laughter of children and the thrill of rides was repurposed for a new cinema and chain restaurants.

Remarkably, even as its doors closed, Metroland’s popularity never waned. Until its final days of operation, it remained one of the top 10 tourist attractions in the UK, a testament to the joy and excitement it had provided for two decades. The end of Metroland marked the end of an era, but its legacy as a beloved destination in the North-East lived on in the memories of those who visited.

The reason why Metroland closed down

The decision to close Metroland didn’t come from a lack of popularity, but rather a strategic choice by the shopping centre’s owners. They concluded that updating and expanding the amusement park wouldn’t be as profitable as dedicating more space to retail. Capital Shopping Centres stated that the redevelopment of the Yellow Mall’s area would continue to prioritise modern retail experiences for both local shoppers and visitors.

As part of this shift, the original cinema at the centre was replaced with additional retail space. In place of the former amusement park, a new cinema emerged, opening in 2010 as part of the Metrocentre Qube. This transformation marked a significant change for the MetroCentre, stripping away much of the unique character that had once set it apart. The once-iconic location in the North East of England, known for its unique combination of shopping and entertainment, had been reshaped into a more conventional shopping mall. The distinctiveness of having an amusement park within a shopping centre, a rarity that added charm and appeal to the MetroCentre, was now just a fond memory.

In a twist of fate, Intu (formerly Capital Shopping Centres Group), the company that had phased out many of the MetroCentre’s unique features, fell into administration in 2020. Owning 17 different retail centres across the country, Intu’s downfall highlighted a lack of distinctiveness in their properties. The MetroCentre, once a beacon of innovation in retail and leisure, then came under the management of Sovereign Centros, an independent real estate operating partner, marking a new chapter in its history.

Metroland’s legacy

Meanwhile, in a heartwarming turn of events, the Metroland roller coaster found a new lease of life. The Big Sheep, a farm-themed amusement park in Northern Devon, resurrected this iconic ride in 2016. After spending eight years in storage, the roller coaster that introduced countless children to their first thrilling ride was back in action. To celebrate its history, The Big Sheep even offered free rides for a time to visitors from the North East of England. Now known as Rampage, the roller coaster continues to delight visitors, preserving a piece of Metroland’s legacy.

Reflecting on the MetroCentre’s origins, it’s interesting to note the initial local opposition. The centre’s inception brought with it American retail concepts, stirring concerns among residents about the impact on British shopping culture. Yet, over time, the mall became an integral part of the North East’s landscape, blending shopping with entertainment in a way that had not been seen before in the UK.

Metroland, initially viewed by some as merely a diversion to keep kids occupied while parents shopped, turned out to be much more than that. To a few, it might have seemed like an elaborate children’s crèche, but over its 20 years, this compact indoor amusement park etched joyful memories in the hearts of families not just from the North East, but from across the UK.

Sir John Hall’s vision had indeed taken flight. People nationwide knew about this sprawling shopping centre up North, one that offered much more than the typical mundane mall experience. It was exactly what Hall had imagined – a place where families could enjoy shopping together in a unique and fun environment, right down to the gnome statues themed after the colours of the mall.

Until 2018, the MetroCentre still held the title of the UK’s largest shopping centre. Yet, many of the quirks that set it apart have since disappeared.

Metroland might not have been the world’s greatest amusement park, but it held a certain charm characteristic of the entertainment centres of the 90s, a charm that’s hard to find today. It was ahead of its time. While the MetroCentre still stands, the essence of what made it a standout destination for both leisure and retail in the North of England seems to have faded away, leaving behind just another struggling shopping centre.

We hope you enjoyed this trip down memory lane and are keen to hear your thoughts on the topic. Did you ever visit Metroland? Do you think it should have remained in operation?

Share your favourite memories of the park with us on our Facebook page. We’d love to hear your stories!